HISTORY OF MARTINEZ'S CRIME ... (

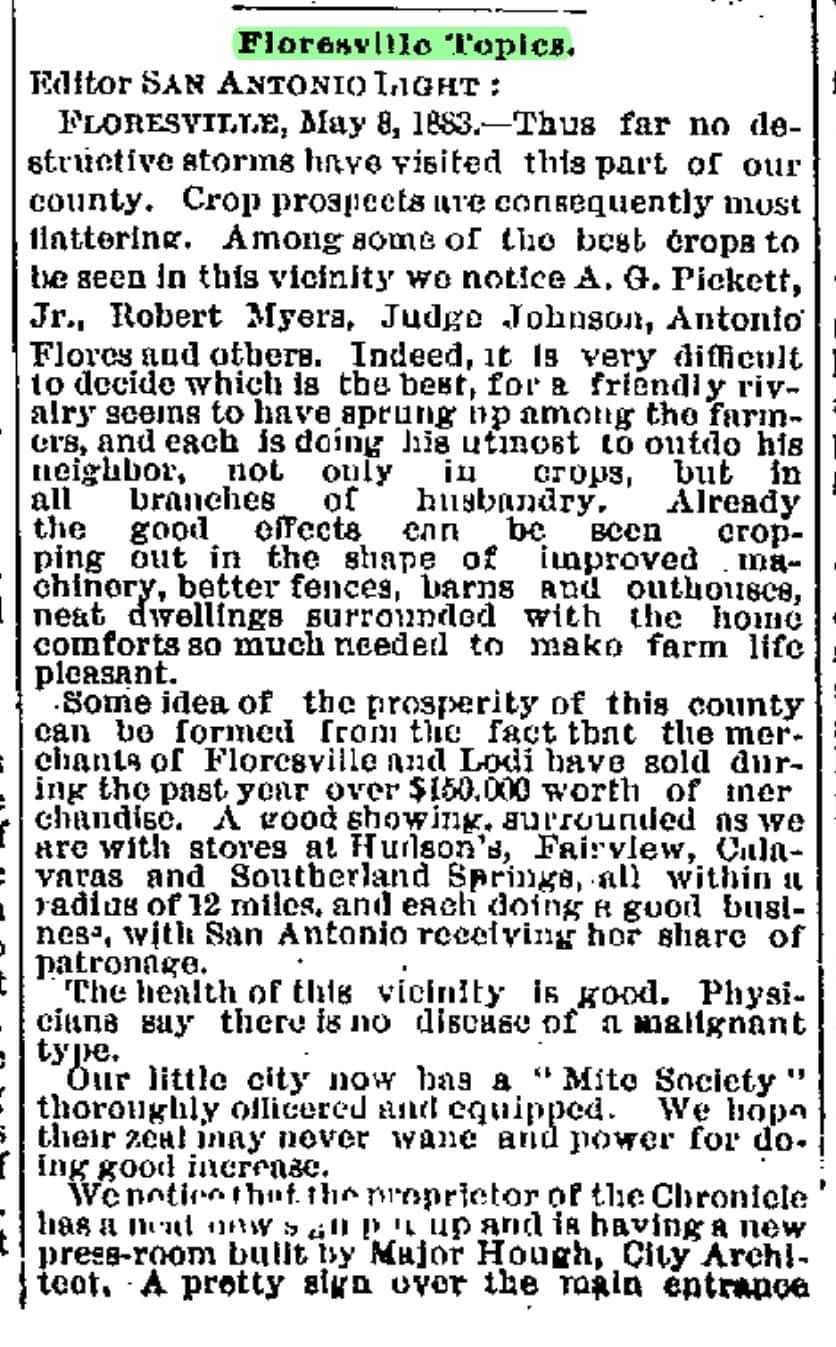

hometownchronicles.com) Manuel Martinez was born about 1820 in Texas, the son of parents born in Mexico (father) and Texas (Mother). Manuel was a farmer and a town constable. He married Teodora Lazarin about 1858. Teodora was born about 1826 in Texas, the daughter of Texas-born parents.Two children of the union: Nicolasa Martinez - born 1858 in Texas and Maximo Martinez - born 1860 in Texas; died 30 July 1897 in Floresville, Wilson County, Texas.

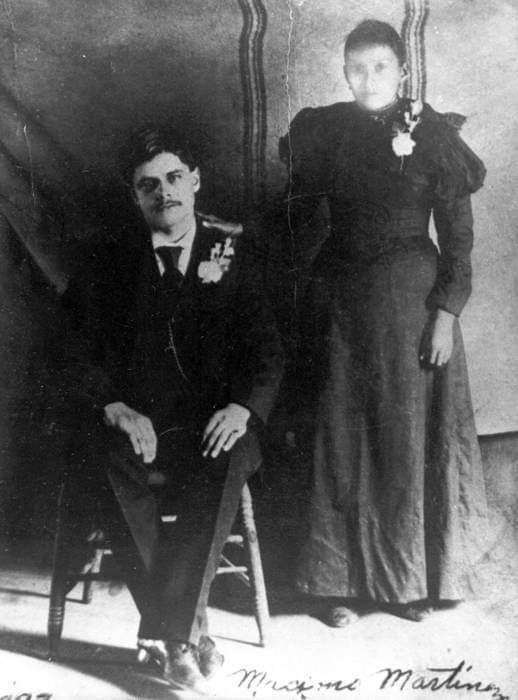

Maximo Martinez was born 1860 in Texas, probably in Bexar County. As a 20-year-old he was still living at home and worked as day laborer in Bexar County. He married Trinidada Martinez in Floresville on 12 September 1894. The marriage brought two children : Dolores Martinez - born 1895 in Floresville, Wilson County, Texas; died 5 Jan 1989 in Poth, Wilson County, Texas and Cevera Martinez.

On the night of June 6, 1897 Maximo changed the lives of everyone around him. His story is given in the newspaper clippings below.

*************************************************************

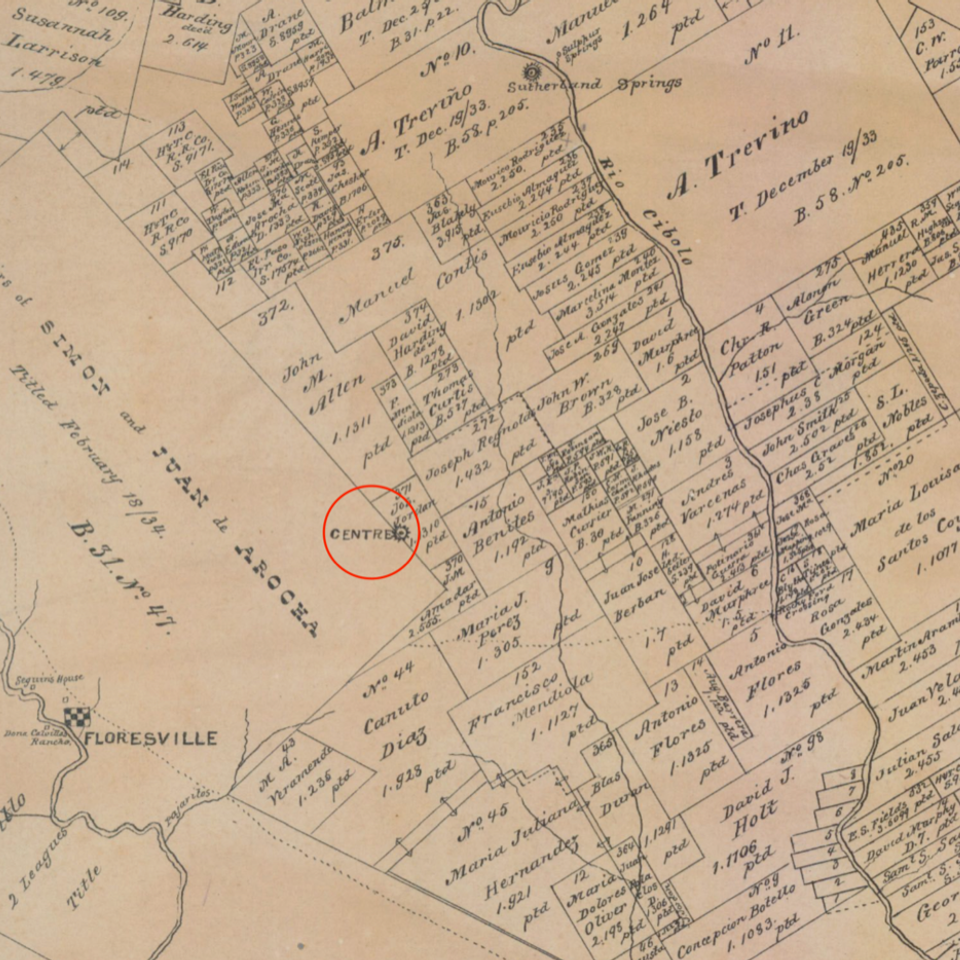

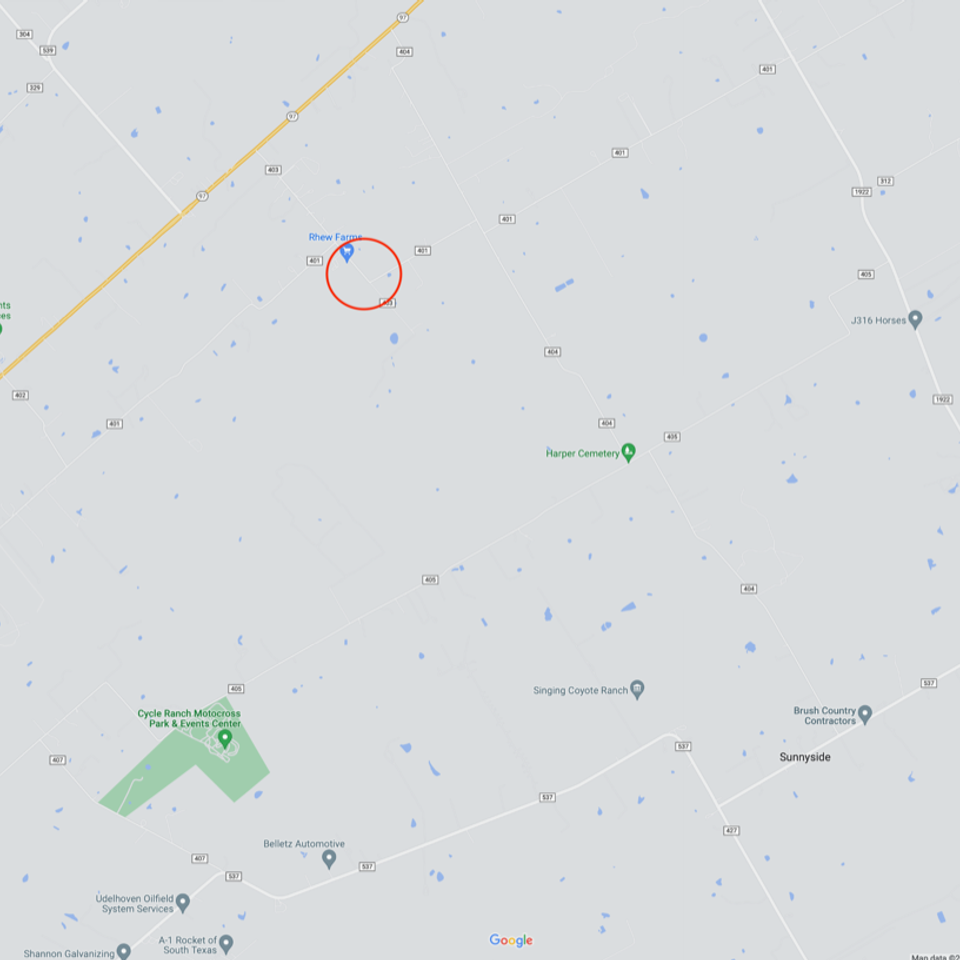

Wilson county people were horrified on Sunday, June 6, when the news of the brutal murder the night before of Plutarco Carrillo, his wife Dolores, and their granddaughter, Juanita Acosta, at their home nine miles south of Floresville, was circulated. The ages of the three were 81, 51 and 18. There were no other members of the family on the place. A grown son of the old couple had been to a dance a few miles distant and returned home at 4 o'clock on Sunday morning. He was the first to discover the horrible crime, and brought the news to Floresville.

Justice H. B. Gouger and Deputy Sheriffs Wright, Sanderfer, Garza and Seale and County Physician J. M. Mason, with others, left for the scene of the horrible affair as soon as possible after the news was received. The old couple slept under a brush arbor in front of the door. They had been knocked on the head with an ax. The old lady died immediately, with one hand resting on her husband's shoulder. The old man breathed a few times after the officers arrived, but was unconscious and never moved.

The object of the murder of the old couple was to get possession of the person of the girl. She was in a room, and resisted the attempt of the brute to outrage her. She was stabbed in the back with a knife, and escaped by way of a window, but was overtaken and stabbed in the breast and assaulted while in a dying condition. She was nude, with the exception of a thin shirt, when the young man returned. He spread a quilt over her and hurried to town with the news.

Judge Gouger examined several witnesses, neighbors of the family, and rendered a verdict to the effect that the three were killed by Maximo Martinez, a well known young Mexican of bad reputation, who lived on a ranch a few miles distant, but who had married near the scene of the murder and had left his wife and two children.

The murderer was named by the young man who brought the news to town. He had made frequent attempts to obtain the girl, but she feared him and had avoided him.

The officers followed the trail of the murderer, who was on horseback to the ranch where he worked and where he changed horses. They then went to Falls City, where Sheriff Morris and others joined them, the sheriff having been notified by wire at Karnes City. From Falls City the officers followed the trail in the direction of Campbellton, Atascosa county, and soon met a mail carrier, who said he had met Martinez in the road and he had told him of the murder. At Campbellton they were joined by officers from Atascosa county and by Manuel and Theodore Tom, the two latter being experts in following a trail. The murderer was now on foot. He had given his pistol for something to eat, and was headed for the Rio Grande. After much labor in scouring the country, the trail being frequently lost, the murderer was surrounded at a ranch in McMullen county and captured. He surrendered to Deputy Sheriff Juan Garza of Wilson county, who knew him personally. On the way back the prisoner confessed everything as told above, except to the outrage of the dying girl.

District court was in session in Floresville. The accused had been indicted for the three murders. He was arraigned on June 23 before Judge N. Kennon, and was defended by J. E. Canfield and L. B. Wiseman. The trial was concluded late at night. Next morning the jury returned a verdict of guilty and assessed the penalty of death. He took no appeal and was sentenced the same day by Judge Kennon to be hanged on July 30 for the murder of Juanita Acosta. He asked to have a band play during his execution, and for permission to see his wife.

***************************************************************

THE CRIME.

On Sunday, June 6, of the present year, a Mexican man, his wife and daughter were murdered at Floresville and Martinez, who had been paying considerable attention to the girl, was suspected. He had asked the girl to run away with him, but she refused and this is believed to have led to the crime.

At any rate, Martinez had been missing since the murder was committed. A posse of officers went in pursuit of him. They hunted high and low. Sheriff Morris, of Karnes county, with a number of others, took the direction toward the Rio Grande, believing that Martinez was headed toward Mexico.

After a five-days' chase they discovered the trail of their man and captured him somewhere near the boundary line of McMullen and Webb counties. He was afoot and shoeless. When he saw that all hope for escape was lost he surrendered and confessed that he was the man wanted. No time was lost in taking him to Floresville, where he arrived in custody of the officers and was placed at the Wilson county jail. A crowd of about 400 people was at the depot to meet the officers and the prisoner, and for a while it appeared as if a necktie party was being organized.

In order to avoid a lynching, the train was stopped before it reached the depot, and the prisoner was quietly hustled off to jail, while the people waited at the depot only to be disappointed.

The posse consisted of two officers of Wilson three of Karnes and two of Atascosa counties. their man was caught on the Osmon ranch in McMullen county by Juan Garza. The accused feared he was going to be lynched and made a full confession to the officers, begging earnestly for protection. He detailed how he killed Plutacho Carillo, age 81 years, Dolores Carillo, aged 51 years and the 18-year-old girl Juanita Acosta, the latter after he had ravished her. He said he would have killed the Martinez family also, including his wife, from whom he was separated, had not daylight come too quickly. He said he loved the Acosta girl and she would not elope with him.

****************************************************************

San Antonio Daily Light June 21, 1897

Front page, col.1

MARTINEZ INDICTED.

He Will Be Tried for Murder at Floresville Wednesday.

It is locally reported that Maximo Martinez, who in the Wilson county jail on his confession to the murder of an old Mexican man and woman and a girl, has been indicted for murder and will be tried in Floresville next Wednesday. A special venue of one hundred men has been ordered from which to select a jury. In order to give Martinez a fair and impartial trial, the court has appointed Messrs. Caulfield and Wisenian, of Lavernia, to represent the defendant.

****************************************************************

San Antonio Sunday Light June 27, 1897.

Front page, col. 5

MARTINEZ IS HAPPY.

He Wants a Brass Band to Play at His Hanging.

Maximo Martinez, who is in the Wilson county jail at Floresville, waiting to be swung in eternity, for the crime of triple murder, is as happy as the day is long. Henry Merritt, who has occasion to stop at Floresville nearly every day, says that Martinez asks but two favors--he wants to see his mother and relatives and wants a brass band to play while he is being hanged. He says he wants to die, but not at the hands of a mob, and only regrets that it is not June 30 instead of July 30 when he will get the noose.

****************************************************************

The Daily Light July 7, 1897.

Page ?, col. 4

A JOYFUL EVENT.

Floresville, Texas, July 7.--(Special.)--A number of citizens have subscribed $25 to pay for a brass band at the hanging of Maximo Martinez, July 30, as requested by him.

****************************************************************

The Galveston Daily News Friday, July 16, 1897.

Page 6, col. 3

A CONDEMNED MAN.

Declares He Will Cheat the Gallows by Suicide.

Floresville, Wilson Co., Tex., July 15.--Maximo Martinez, the condemned murderer, who is to be hanged on July 30, declares he will suicide in jail before the time for his execution arrives. If no other means of killing himself is presented, he declares he will knock his brains out against the walls of the steel cage in which he is kept. A metal plate was taken away from him this week which had been cut in half, leaving sharp points and jagged edges.

***************************************************************

The Galveston Daily News. July 31, 1897.

Page 2, col. 3

HANGING OF MARTINEZ HE RADIATES A TRIPLE MURDER. WILSON COUNTY'S FIRST LEGAL EXECUTION.

FOUR THOUSAND SPECTATORS.

MARTINEZ EXHIBITS GREAT NERVE ON THE SCAFFOLD--HE SINGS AND TALKS.

A REVIEW OF THE AWFUL TRAGEDY

Two Old People Killed in Order That He Might Get Possession of an 18-Year-old Girl.

Floresville, Wilson Co., Tex., July 30.--Before 9 o'clock this morning the town of Floresville was in a high state of excitement. It was the day set for the execution of Maximo Martinez, the murderer of Juanita Acosta on the night of June 6. The ____ of execution was __ed by Sheriff Craighead at 2 o'clock, but it was twenty-four minutes after when the body dropped from the scaffold, a distance of seven feet. The murderer's neck was broken and life was pronounced extinct in twenty minutes by Dr. Mason of Floresville and Dr. Plekett of Karnes City.

It was as neat a job of hanging as ever occurred in Texas and Sheriff Craighead deserves credit for it. It is estimated that there were 4000 people around the jail and court house to witness the execution. A very large per cent of those present were Mexicans, and few of the number felt or expressed any sympathy for the murderer. Before the noose was adjusted he sang a song, then made a speech, and sang another song. The nerve of the man was something unparalleled in the history of criminals in Texas. He thanked the officers and called the names of several he knew, and finally said good by [sic] to all.

Father Vento, a Catholic priest, was with him to the last moment, and prayed for him as the drop fell. This is the first legal execution wish ever occurred in Wilson county.

***************************************************************

Caller.com, Corpus Christi, Texas

Floresville hanging

In 1897, a farmworker, Maximo Martinez, killed three members of a family near Floresville with an ax. He was arrested in Duval County, returned to Floresville for trial, convicted and sentenced to be hanged. On hanging day, they gave the condemned man whiskey in a tin cup and kept refilling the cup. From his jail cell, Martinez made speeches and sang songs.

W. L. Wright, who was deputy sheriff before he became a Texas Ranger, was there. He later told Bob McCracken of the Caller: "It was a gala day in Floresville when the murderer was hanged. Everybody turned out; there must have been 4,000 people there."

Salesmen worked the crowd. A gramophone salesman played records. A fire extinguisher salesman put up a small model house in the street, then set it afire so he could put it out with his extinguisher. Some didn't know it was a demonstration and began to run. One man yelled, "Keep your seat; there ain't no fire!" Another ran by, shouting, "You're a damned liar!"

At the scaffold, Capt. W. L. Wright put a black cap on the condemned man's head and fixed the rope. Wright forgot to move away from the trapdoor. He managed to jump aside at the last second when it was sprung. Wright said it would have been like the two Rangers who hanged a man in Brownsville and forgot to get off the trap door. "When the trap was sprung, they went through it, too; fell six feet to the ground."

*************************************************************

Bertha Guevara lent this 1897 photograph to "The UTSA DIGITAL LIBRARY" of Maximo and Trinidad Martinez both wearing corsages. Some believe that this photo was taken shortly before he was hanged outside jail in Floresville, Texas, the last hanging in Wilson County.