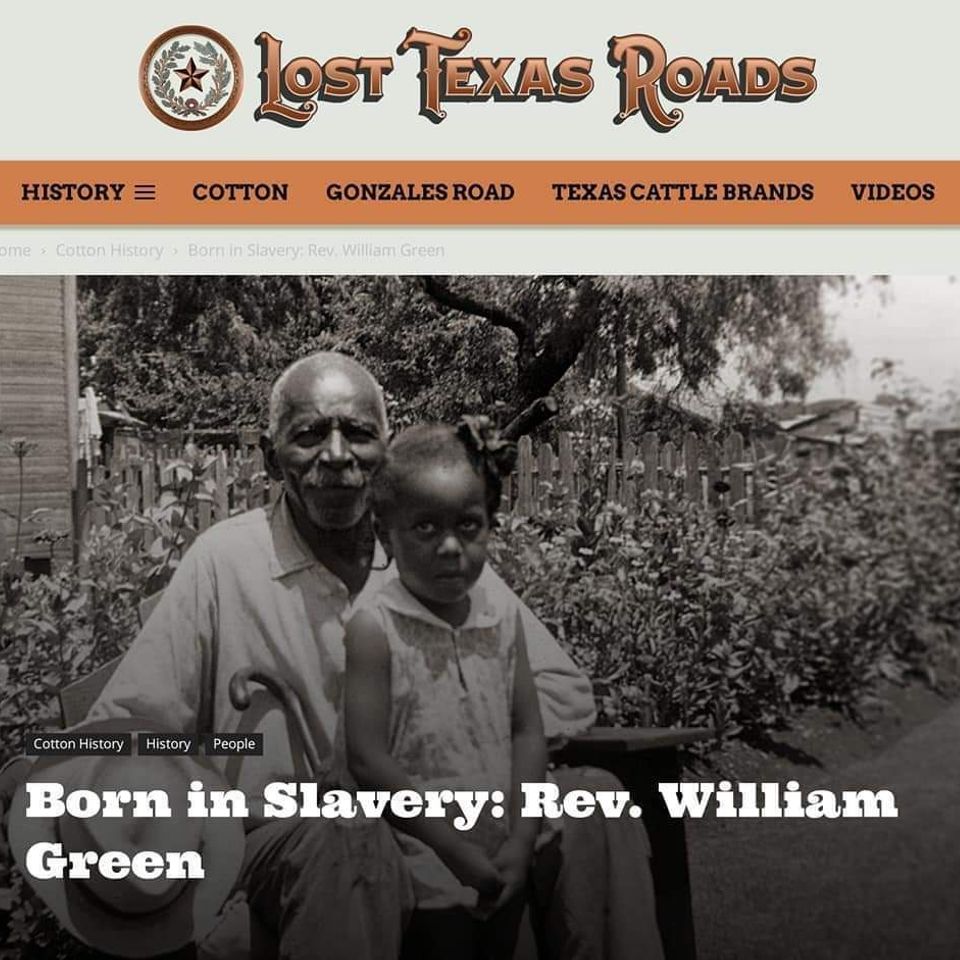

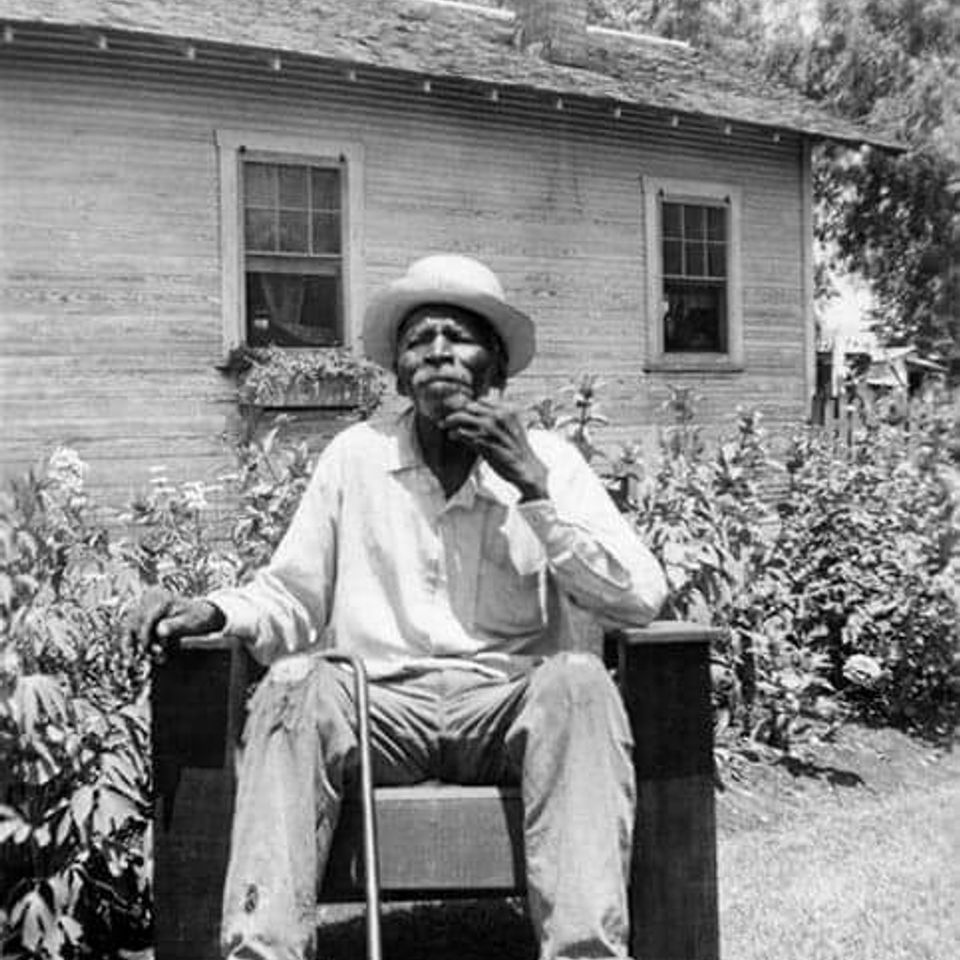

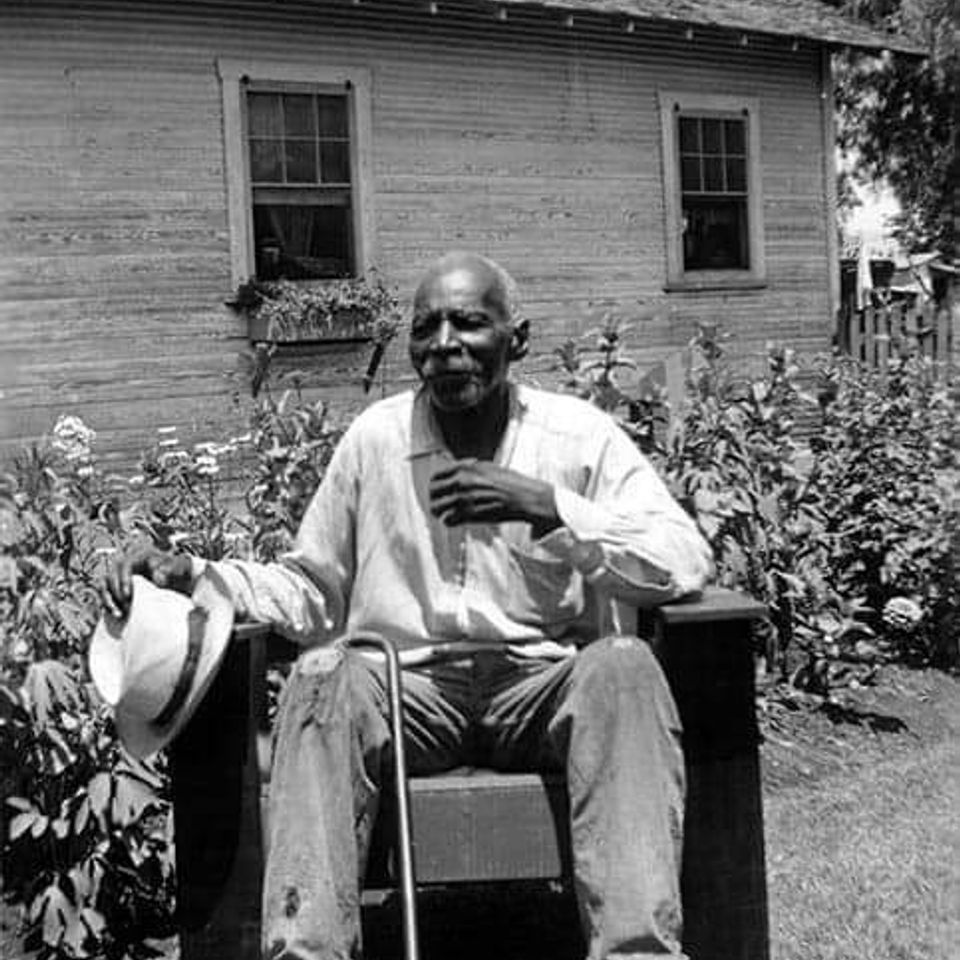

Born in Slavery: Rev. William Green

Narratives from the Federal Writers' Project 1936-1938

From the Library of Congress

Interview of

Rev. William Green (ex slave from San Antonio, Texas – July 1937)

WILLIAM GREEN, or "Reverend Bill", as he is called by the other African-American , was brought to Texas from Mississippi in 1862. His master was Major John Montgomery. William is 87 years old. He has lived in San Antonio, Texas, for 50 years.

"I is Reverend Bill, all right, but I is 'fraid dat compliment don't belong to me no more, 'cause I quit preachn' in favor of de young men.

"I kin tell you my 'speriences in savin'- mis'ry dat was, is peace dat is. I tells you dis 'spite of bein' alone in de world with no chillun.

"I is raised a slave and 'mancipated in June, but I 'members de old plantation whar I is born. Massa John Montgomery, he owned me, and he went to de war and git kilt. I knowed 'bout de war, though us slaves wasn't sposed to know nothin' 'bout it. I was livin' in Texas then, 'cause Massa John moved over here from Mis'sippi. In dat place niggers was allus wrong, no matter what, but it was better in dis place. We used to think we was lucky to git over here to Texas, and we used to sing a song 'bout it.

"I don't know what de song meant but we thought we'd git free here in Texas, and we'd git eddicated, and dat's de meanin' of de talk about writin' and cipherin'.

"Well, when I is free I isn't free, 'cause de boss wants me and another boy to stay till we's 21 years old. But old Judge Longworth, he come down dere and dere was pretty near a fight, and he 'splains to us we was free.

"'bout five year after dat I takes up preachin' and I preaches for a long time, and I works on a farm, half and half with de owner. I was a good life, but now I's too old to preach. His first preaching was done in Lavernia.

William Green, "Reverend Bill" as he is called in the East Side African-American section of San Antonio, came as a slave to Texas from Mississippi during the second year of the Civil War. His master was Major John Montgomery a wealthy plantation owner of Brook Haven, Mississippi.

My life story can be summed up in a nut-shell: Misery dat was, is peace dat is.

He is eighty-seven years old, and when a boy of twelve, was a cowboy and "a buckerman along side de best of 'em". He has been a resident of San Antonio for fifty years and is greatly looked up to by the African-American . In spite of no education, he has acquired a fluent and vivid power of description. This old African-American's reminiscences are colorful and of value, because they offer comparison between a slave's life in Mississippi and Texas.

I is Reverend Bill, all right; but I am afraid dat compliment don't belong to me no more. I got old and quit preachin' in favor of de young men. The good book says: "Old men for council and young men for War'. My life story can be summed up in a nut-shell: Misery dat was, is peace dat is. I tells you dis in spite of me being alone in de world with no children given to me by either of my two wives. Dat's where I live, in dat little gray shanty over there. I just come over to Mrs. Fentress on a visit.

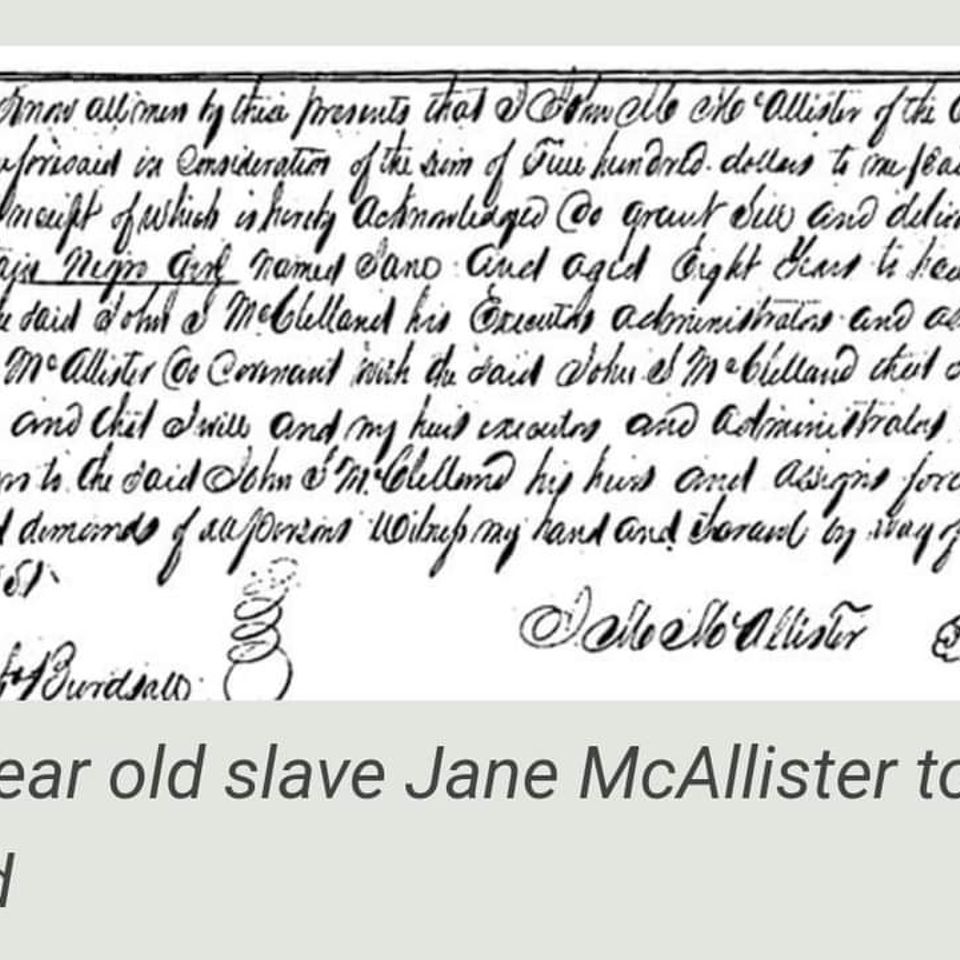

Brook Haven in Mississippi was de place where I was born. It was eighty-seven years back. I was raised there on a plantation of my master's, Major John Montgomery. He went to the war and got killed. After that the family sells a lot of slaves. They sell my mother too. They didn't mind separatin' children from mothers anymore than a calf from a cow.

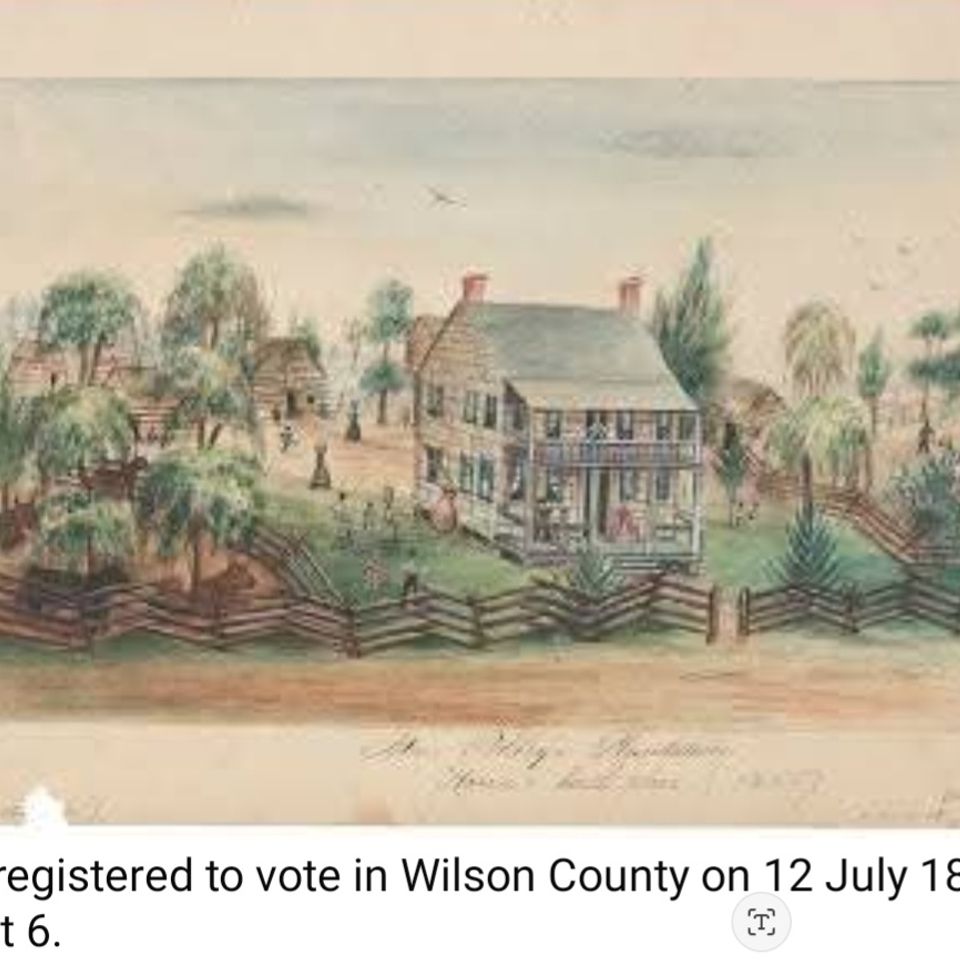

We comes down to Texas and got a ranch at Lavernia. Our farm was a ranch where they raised and trained wild horses. The horses was of Spanish and American stock. I was a buckerman yes, buckerman-I never heard of buckeroo until I knocked around quite a bit. By the time I was twelve, I could break horses along side the best of 'em. We lived tolerably fair.

They wasn't as mean to us as they was to a lot of slaves, but we got our share of suffering. They whipped us with straps and not black bull-whips, like they used in Mississippi. Our food was better. We had meat-bacon, and sometimes beef. And we always had cornbread.

I remember when the war started. I remember the red stripes down the grey trousers, and I also remember some yellow stripes. I can see the soldier's legs a-moving. Us slaves wasn't supposed to know what was goin' on. But we didn't have enough education to understand it even if they did tell us about the reason for the war.

When I heard it was to free the African-American , I didn't take it as if I was one of de African-American men to be freed. I thought of me as an African-American . I thought they must be talkin' about some other African-American that was far-away, maybe, as Mars.

All I could read was the brands on horses. Our brand was JMJ. Very few slaves in Wilson County knew what the war was about even after it was over. No change in our lives happens for six months or maybe two years after the war. The Yanks had to come down all through the country before they lets us loose.

I was only fourteen when the war ended, and my boss tried to compel me and another boy to stay on until we was twenty-one. Him and me was the only ones dat was young slaves. If it hadn't been for ole Judge Longworth, I might have been a slave for seven years longer by way of a contract my boss wanted to draw up. Judge Longworth, he come over and dere was pretty near a fight. He was a little man but he tole de boss just where matters stand, and he explained to me dat I was free.

But even knowin' I was free, I wasn't free. You'll know how dat was when I tells you what happen' one day sometime later. Me and this other boy steals some melons and got seen doin' it. I knew the kind of beatin' I was goin to get and I jumps on a horse and runs away. I passes people and dey didn't know I was runnin' away. I was a right schemin' rascal, and I tole dem I was goin' to meet a white man.

Well, I gets hungry long about evenin' and I rides up to a house not far from Lavernia. The folks in the house catches me and say, "He's one of Montgomery's slaves. "Everybody all around recognizes whose slaves African-Americans was. I tell 'em I was free, and they laughed. Then they took me back. What a whippin' I got! Now, I deserved a whippin', maybe, because I stole the melon, but they was stealin' me and makin' me a slave when I was no slave. They tied me up to a tree and was beatin' me when a white man comes along and says dat he was goin' to report dem. They says, "Go ahead", and they beats me all de more for it. It must have been a powerful beatin' cose I remember it above all my suff'ring.

I tell 'em I was free, and they laughed. Then they took me back.

I'll tell you another thing to let you know dat slavery went on after de war. It also shows dat slaves takes up and fights for demselves sometime, like they never did in Mississippi. One day they got a new overseer on a ranch nearby, and de master tells him dat one of his African-Americans is a good worker but dat he won't take no beatin'. He tells him not to whip him. Well, dat was de slave dat the new overseer decided to whip first.

He lays in onto him powerful bad. When the night comes, the slave goes over to the overseer's house, knocks on the door, and says dat he has a message from his master. When the overseer opens the door, the slave cuts his throat from ear to ear; he falls down on the ground dead. Then the African-American goes and tells his master what he done. The master gives him a horse and saddle and tells him to ride. He tells him to ride hard across de border. De African-American must have made it into Mexico all right, cause we never heard no more about it.

"I never hear of a slave fightin' and rebellin' in Mississippi, I hears of jails for African-American up North, though. We never has no jails here. The Texas white man looks on African-American more accordin' to the African-American . If he was strong and good, he was respected for that.

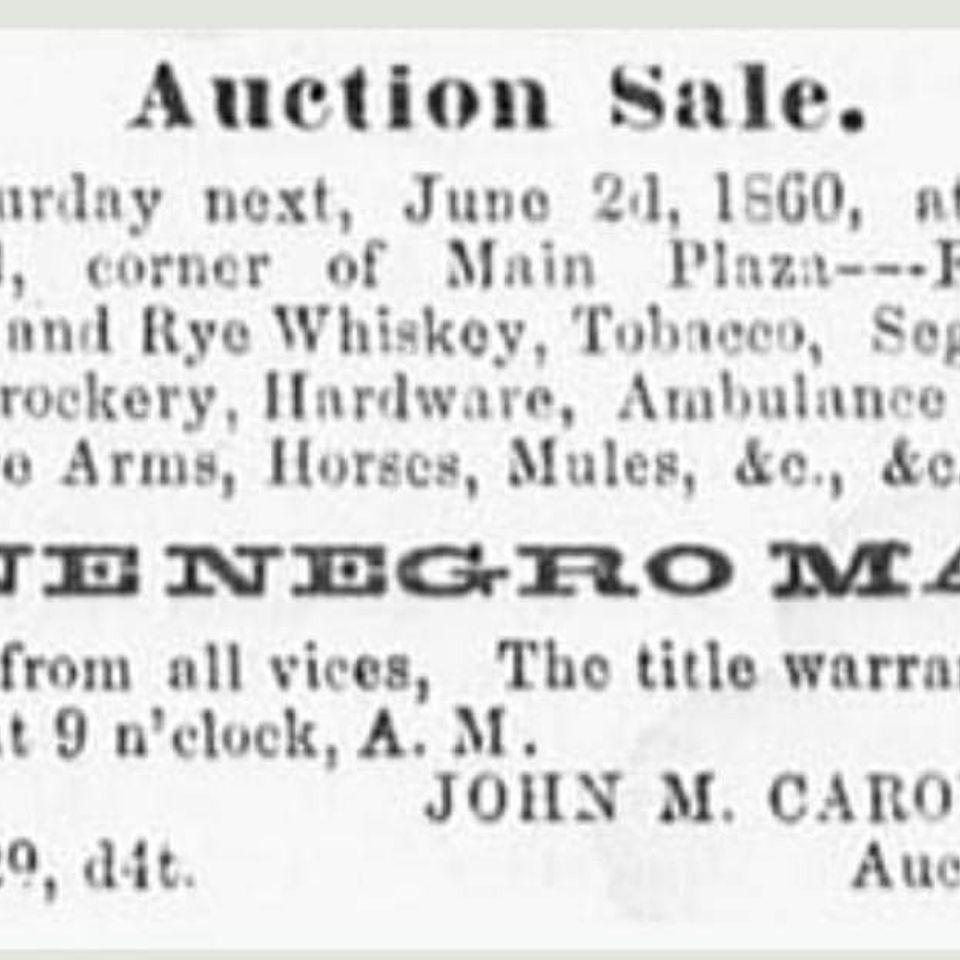

In Mississippi, African-American was always wrong no matter what. No white man would help him against a white man as they did when the African-American killed the white man down here in Texas. Then higher prices was paid for slaves here. I heard of one slave, a good blacksmith, who was bought in Texas for $2,500. In Mississippi, $500 was a good price. We slaves who had come down to the South from the North got to think that we was lucky to be in Texas.

At the end of the narrative "Reverend Bill", diplomatically, brought out that he thought he should be paid for including the song in his reminiscences; There ain't nobody, he explained, dat recollects de words but me, and de Lord gives us memory to be recompensed."

Note: This narrative has been transcribed as it was originally written. John T. Montgomery came to Texas from Starksville, Mississippi; he appears in the 1860 U.S. Census in Guadalupe County, Texas (Lavernia P.O.). On March 26, 1862, he enlisted in Seguin, Texas with Capt. John Ireland's Co. of Volunteers (Co. K, 8th Texas Infantry). He entered the CSA army as a private and was a private when he was discharged in March of 1865 at Galveston, Texas. He had previously served with the Cibolo Guards; it is possible that he attained the rank of Major with this organization. John T. Montgomery died in 1903; he is buried in Concrete Cemetery in Guadalupe County, Texas, just north of La Vernia.

*********************

(Courtesy of Allen and Regina Kosub of "LOST TEXAS ROADS" )