by Barbara J. Wood

Freedmen – Black and White

In December 1854, James P. Newcomb, a newly minted publisher, watched as San Antonio and surrounding Bexar County became the home of immigrants from Europe and other parts of the United States. In 1854, the 17-year-old Newcomb began publication of the Alamo Star. Newcomb's long and colorful career would produce a long list of publications that included the San Antonio Herald, the San Antonio Alamo Express and the San Antonio Light.

Two groups of people caught his attention and he reported their arrival in his Alamo Star.

"We are informed by a gentleman that three families have lately moved to the Cibolo, in the neighborhood of Mr. Neil's, having an hundred african-americans. They say there are several families on their way out here with a large number of African-americans, this is the kind of immigration we like to see."

– December 11, 1854

"Beggars – Our city has lately received a supply of beggars from Poland. These individuals whether in real want or not, tell very distressing tales. They are robust and healthy and able to work."

– December 25, 1854

"The plantation owners with their African slaves settled on the Cibolo. And about 20 of the families from Polish Silesia settled among the Cibolo plantations. With silver and gold coins they brought with them from Poland, they purchased a portion of the Charles G. Napier Plantation and created a settlement that would become St. Hedwig, Texas."

Within a few years, Bexar County would be would be drawn in to the cataclysm of the Civil War. In May of 1861, the Knights of the Golden Circle and Confederate Rangers destroyed James Newcomb's newspaper. He fled to Mexico and then sailed to San Francisco.

The Polish of Bexar County were pressed into military service. From the small community of St. Hedwig, 19 men served during the Civil War. Their immediate neighbors were leaders of the Confederacy. Colonel E. H. Cunningham would lead an elite element of Hood's Texas Brigade. General R. W. Brahan was a delegate to the Secessionist State Convention and later in charge of conscription for the 30th Texas Militia.

"Confederate newspapers in San Antonio wrote that "open graves" awaited them upon their return."

The Polish were reluctant participants. One of the their reasons for leaving Poland was the interminable military obligation imposed on them by the Prussian government. Several of the Polish were military veterans who understood the aftermath of war and did not share their neighbor's enthusiasm to fight. The Polish did not sympathize with a cause they did not understand.

Not a single battle of the Civil War was fought in Bexar County. However, the planters and their allies, after forcing the surrender of U. S. forces in San Antonio, on February 16, 1861, created military units that marched north to the killing fields. They were in Virginia by the fall of 186.

"On June 19, 1865 (Juneteenth), Union General Gordon Granger from Galveston, Texas issued General Order Number 3 informing the people of Texas "...all slaves are free...""

To the planters and their allies on the Cibolo, the Polish and the freed African slaves were both viewed with suspicion. Many of the freedmen came into the Polish settlement where their number's were sufficient to catch the attention of San Antonio newspapers.

The San Antonio Daily Herald reported on May 28, 1867:

"...Last Friday night a big meeting was held on the Cibolo, at Napier's old place, where were congregated a large number of freedmen black and white, and where two hundred and forty-four were enrolled...."

The vigilante violence of the post-Civil War era visited the Cibolo. The most notable was the murder of a freedman at the nearby village of Lavernia by the Taylor Gang associated with DeWitt County. Members of the Gang reportedly ran the man down with their horses and shot him dead.

The result was Bvt. Major General Charles Griffin, U.S. Army, on July 16, 1867, issuing a seize and kill order for members of the Taylor Gang which the Army believed was constituted of 20 to 50 members.

Another event that speaks of the era of vigilante violence was the actions of the planters that caused a mob of freedmen to descend on the village of nearby Lavernia and remove from custody one of their own. The freedmen reported the incident to Major Whittmore of the U. S. Army in Seguin, Texas. A contingent of U. S. Cavalry under the command of Lieutenant Clemens was sent to Lavernia to settle the affair. Lieutenant Clemens lectured both the freedmen and planters ordering that they defer to the legal authority and that vigilante action by either group would not be tolerated.

The gangs continued to operate in the area with impunity. However, the Polish settlement on the Cibolo took a different approach to the gangs. On March 23, 1868, days before the community prepared to dedicate the cornerstone for their new church, members of the gang attempted to rob the Mihalski store.

In the middle of the robbery, the storeowner blew out the lantern and a fight ensued. Felix Tudyk, 73-year-old patriarch of the community, entered the fray with an ax handle and clubbed one of the robbers to the ground.

Before he could deliver a second blow the robber shot Felix through the arm. The gang fled with only a few coins. The newspapers reported that a freedman had sounded the alarm.

Before the Civil War, the planters viewed the Africans slaves as a valuable resource for producing cotton and tended to their needs. After the Civil War, they viewed them as unpredictable, unreliable; and to many, a nuisance. Without slave labor, the Cibolo plantations failed and the Africans were left on their own.

Before the Civil War, the Polish had registered their cattle brands, cleared land and engaged in subsistence farming; selling their eggs, butter, produce and cord wood in San Antonio. After the Civil War there was little money and the Polish found the markets for their goods in San Antonio depressed.

However, at the close of the Civil War the demand for cotton was greater than ever. The Polish and the Freedmen found a common interest: cotton production.

Before the Civil War, cotton growing was confined to the slave-owning plantations. The Polish who came from the Upper Silesia area of Poland had no experience with cotton culture.

However, the Freedmen who were brought to the Cibolo from the Old South were experienced at bringing in this valuable crop.

Willing to work and with large families, both the Freedman and the Polish could place large numbers of hands in the field. This informal alliance based on a common interest brought prosperity to the east Bexar County community.

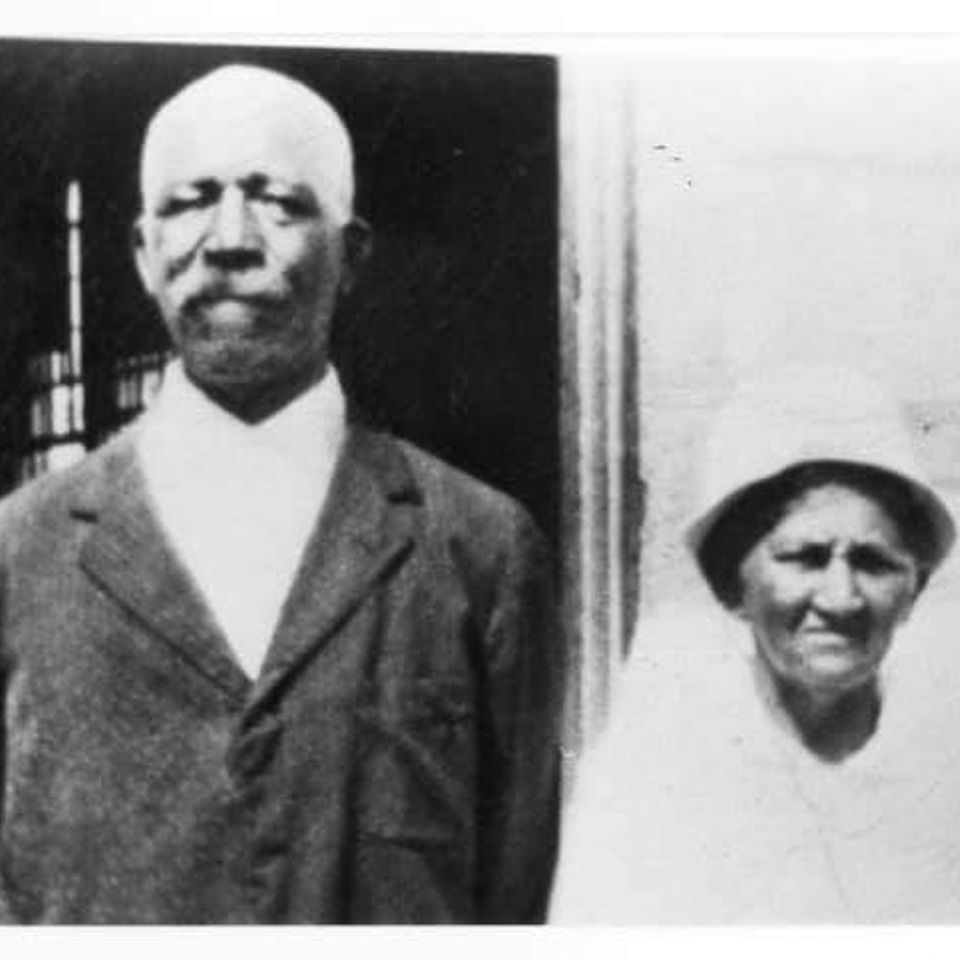

The African Freedmen congregated in and around the community that was finally named St. Hedwig in the late 1860's. The Haywood brothers (Tecumseh, Alex and Hannibal) bought 100 acres of land in the community adjacent to the Mihalski farm for $300 in specie. This was one of the earliest purchases of land by freedmen in Bexar County after the Civil War. They registered their cattle brands with the Bexar County Clerk and reported their grazing land to be in the "Polander Settlement."

An article in the San Antonio Daily Express, Monday, September 27, 1875, titled "Country Jaunt" created a vivid image of the community:

"...At 11 o'clock, we arrived at what is commonly known to San Antonians as Polander Settlement, but called by those living there, St. Iadoiga (St. Hedwig). It is very pleasantly situated on the West edge of a growth of post-oaks, and shows a much greater evidence of life and prosperity than we had looked for. Upwards of sixty families are settled in the neighborhood, most of them being Polish and african-americans, and nearly all of whom follow the plow successfully as agriculturalists. There is a very fine Catholic Church here built in 1869, of hard rock, and also a good two-story school house, also a hard rock structure, almost as large as our Flores Street Free School building, besides six stores, a lumber yard and a shoemakers shop.

Arrived in the middle of town, we tightened our ribbons in order to better come at the situation of things. As soon as we stopped, about a dozen large african-american boys came up and surrounded the ambulance, casting scrutinizing glances at our out-fit in general, but particularly at the horses, which conduct was not understood by us at first. Directly, however, they all sat down together on a sand-bank, smoothed it over, and began to make photographs of the brands on our horses, in the sand, with their fingers – they were brand students. This is a department of knowledge the city denizen know very little about.

Cotton is the main product of this section – we noticed fields of it all along the road. Like all other plants, it was stunned by the summer drought, and only now is getting under headway to make anything, it being full of young bolls and blossoms, but the people fear early frost..."

The Polish and African settlers prospered during the 1870s and 1880s. The Polish began to purchase the abandoned plantations along the Cibolo and other lands surrounding the community. These acquisitions would be reflected in the incorporated boundaries established for St. Hedwig in the 20th century. In Bexar County, St. Hedwig is second in area only to San Antonio.

Galveston News, Friday Decenber 24, 1869 reported:

"...A lot of cotton raised in what is known as the Polander settlement on the Martines, near San Antonio, passed through the later city en route for Mexico on the 17th inst. The editor of the Star learned from the owner that over 200 bales had been raised by the Polander settlement, and thirty-five bales being raised by one man, and the average had been over a bale to the acre. The informant himself raised six bales to five acres, and from one acre he obtained two bales of 473 and 313 pounds respectively after deducting the ten percent for ginning..."

San Antonio Express. July 30, 1879 reported:

"Bexar's First Bale – The first bale of cotton raised in Bexar county this season was brought to the city and placed on the market yesterday by Tecumseh Haywood, a colored man, who resides on the Martinez. The cotton was ginned by Jesse Jones. It was purchased by L. Moke & Bro. for 11 cents (per pound) and shipped by them to Marx and Kempner, Galveston."

Jim Crow laws were never seen in St. Hedwig. Activities directed at the Africans by vigilante and terror groups like the Ku Klux Klan were not tolerated. Africans could trade freely at community stores, the blacksmith, cotton gins and saloons.

Members of the Polish community donated land for an African school. The African Haywood family provided land for the African Cemetery known today as the St. Hedwig Cemetery.

Both the African and Polish communities produced their share of miscreants, cattle rustlers and outlaws. And both produced their share of notables.

When descendants of both communities speak of the other, a common phrasing emerges: "they are just people, they are our neighbors."

****************

COURTESY/ Lost Texas Roads by Allen & Regina Allen Kosub. Allen and Regina have worked with communities and historical organizations to reveal important properties and have them designated by the Texas Historical Commission as "historic properties."