Cibolo Valley

Historians struggle to identify sources of information that have first hand knowledge..... Eyewitnesses to historical events are treasured "primary sources". On Sunday, October 22, 1905 an article by J. B. Polley appeared in the San Antonio Daily Express describing the settling of the Cibolo River Valley. In 1847, as a boy, J. B. Polley came to the Cibolo River Valley with his father the legendary J. H. Polley. J. H. Polley came to Texas in 1821 as one Stephen F. Austin's original 300 settlers.

This article chronicled in some detail the arrival of various settlers and the locations of significant landmarks. Although the article contains racial characterizations, it is offered here unedited for historical accuracy.

OLD TIMERS ON THE CIBOLO

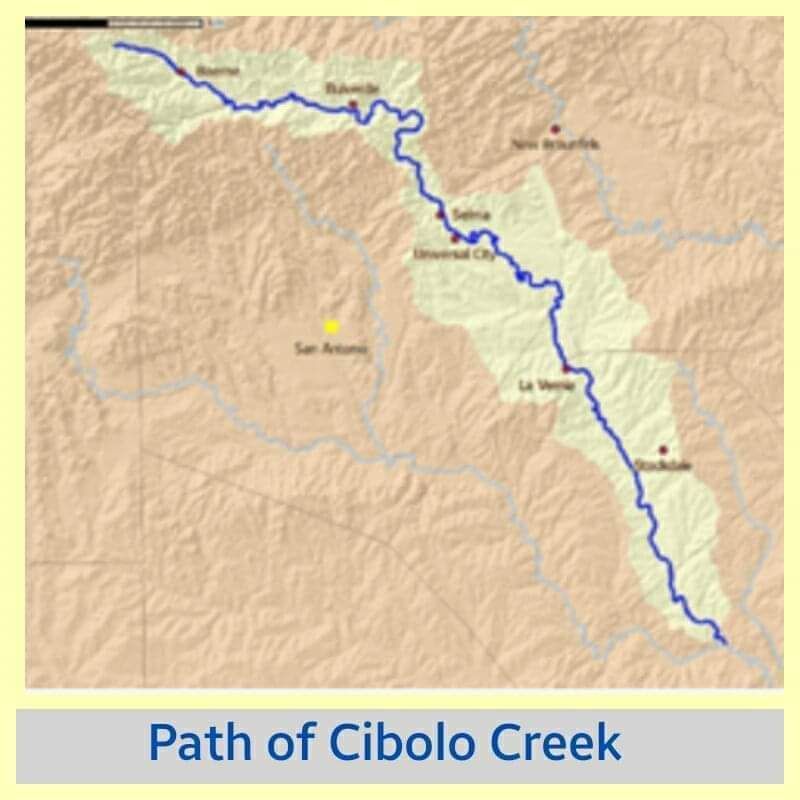

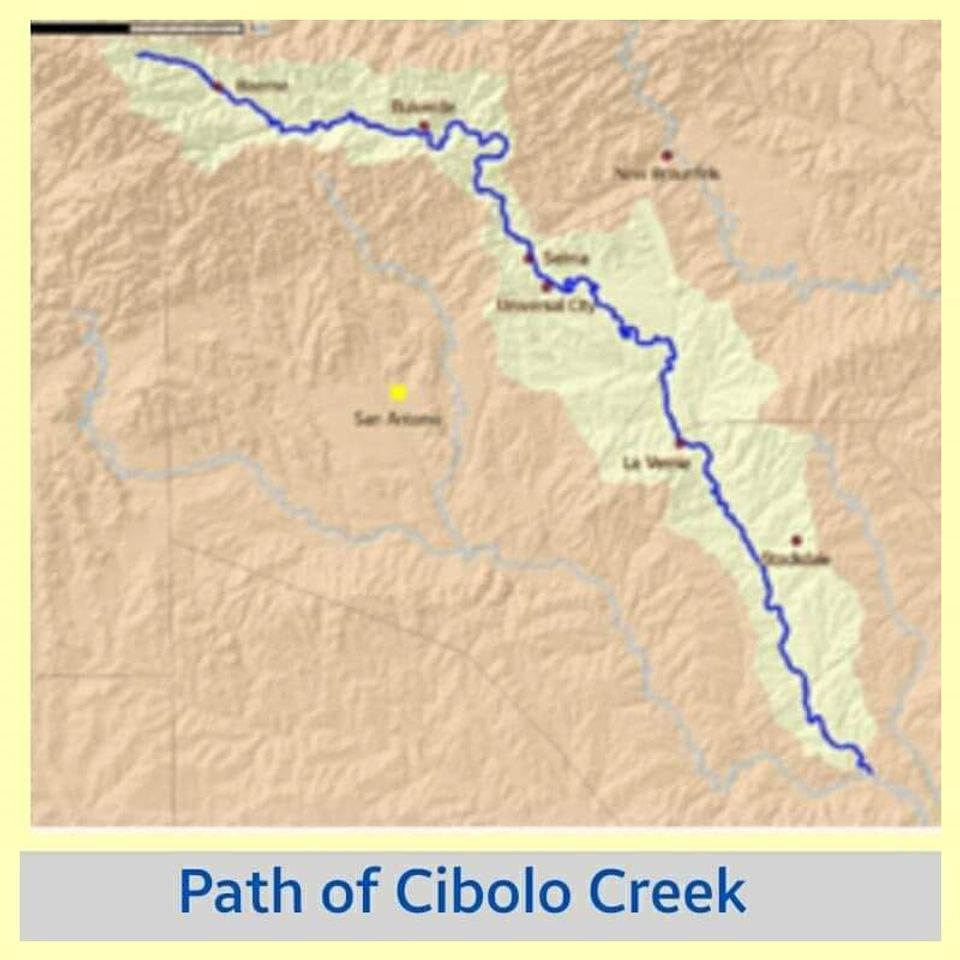

In the year, 1847, San Antonio stood thirty miles out in the wilderness broken west of the Guadalupe River, by only a few, far-between habitations of white men. There was a small, narrowly confined settlement at Castroville, on the Medina; twelve to fifteen ranches along the valley of the San Antonio River extending down to the site of present day Floresville; a stage stand at the point on the Cibolo Creek where the road from Seguin to San Antonio crossed it and a ranch owned by the Caravajal family, located fifty miles below the stage stand at the point where the La Bahia Road crossed the stream.

On the Comal, a beautiful little river, not three miles long, a colony of Germans had established themselves, the place now being known as New Braunfels. On the east side of the Guadalupe River, thirty-five, seventy-five and one-hundred miles from San Antonio, respectively, were the small towns of Seguin, Gonzales and Victoria, and at intervals between these were a few widely separated farms and ranches. Cuero was not then in existence, Helena, not dreamed of by the wildest imagination. Opposite Sequin was the Flores Ranch opposite Gonzales, perhaps another ranch – it was ninety miles to Goliad, 100 miles to San Patricio and 150 to either Laredo or Eagle Pass.

But wilderness as was the immense unoccupied territory beginning on the west bank of the Guadalupe River and stretching south and west to the Rio Grande, and north, practically to the Artic Ocean, large portions of it were to the eye veritable paradises of promise and none more so than that part of land of the valley of the Cibolo, lying below the stage stand at the crossing of the Seguin and San Antonio Roads. It would be difficult to convince a person who never saw the valley until it was covered by a dense growth of mesquite, chaparral, and prickly pear, that up to 1852 it offered to the view a landscape of unsurpassed loveliness.

Averaging a mile and a half in width; divided longitudinally into east and west valley by the stately pecans, elms, hackberries, sycamores and cottonwoods which, growing close to the water's edge and in narrow aprons, bushes and shrubs, green or russet, according to season, the meandering and often tortuous course of the stream; the level surface, as far as up and down as the eye could reach, dotted by such lonely mesquite trees as had withstood the ravages of prairie fires, by motts of elm, hackberry and haw, and the groves of majestic, wide spreading live oaks, fringed by the verdure clad hills to the east and west that marked the beginning of the uplands, and enlivened by the countless thousands of cattle and horses, and scarcely wilder deer which grazed on its thick and luxuriant coating of nutritious mesquite grass it presented a panorama of natural beauty the like of which will never again be witnessed by human eyes.

The Frontier

For time whereof the memory of man ran not to the contrary it had been a chosen range for the buffalo, a favorite hunting ground for the tribes of wild Indians (illegible) ford where shade was abundant (illegible) stood in 1847 the (illegible) frames built of dogwood saplings over which the Indian squaws had stretched the skins of buffalo and deer as protection from the rains of summer and the cold of winter, and around these were scattered many arrowheads of flint and fragments of rude pottery were signs that told as plainly as words that here savage warriors had rested from the toil of hunting and the excitement of battle.

But as peaceful as the valley looked in 1847 and has since remained, there was an abundance of signs to prove that it had been the theater of many a fierce and/ sanguinary encounter between the Indians and white man, the Mexican and the American. At many places along the valley, now in the somber shade of mott or grove and again out in the open ground under the scorching heat of the sun lay the whitened bones of human beings — the skulls so widely scattered that one's horse frequently stumbled or shied at them, and the children of the first white settlers sometimes actually made playthings of them. To the negroes brought into the valley by their masters they were horrors to be given wide berth.

The stage stand mentioned above was, in 1847, the uppermost settlement on the Cibolo. It was kept by a gentleman of education and high standing, who because of a slight lameness, was generally known and referred to as "Limpy Brown". Two or three years later he disposed of his holdings to Major——Perryman, and moved a few miles up the creek, established a home at which he was living at the close of the war between the States. Members of his family are said to be living in San Antonio. Below the stage stand, (illegible), the Carvajal Ranch at the crossing of the La Bahia or Goliad Road, the only evidence of any occupancy of the valley by civilized people was the red sandstone walls of a single story, two-roomed building which stood on the west bank of the creek directly opposite the large sulphur spring near present day Sutherland Springs.

The tradition of the day as voiced by the oldest Mexican inhabitants of San Antonio though silent as to the date of erection told that it was an outlying mission established by the same Franciscan Fathers under whose supervision the west bank of the San Antonio River was lined with missions from the city at its head down to Goliad. That it had been long abandoned by its founders was disclosed by the fact that although its walls and roof were in passable repair its only occupants for many long years had been the Mexican rancheros and their families from San Antonio River who had come to drink of and to bathe in the healing waters of the nearby spring. The larger room of the building had been used as a chapel and the massive iron key to the lock of its door was found by an old darkey, and is the possession of a member of his family.

About 1850 the walls tumbled down and the rock of which they were composed was hauled away and put into chimneys. Today two or three piles of pulverized sandstone are all that is left to identify the exact site of the old mission.

The first white people to settle on the Cibolo below the stage stand and above the Carvajal Ranch, were brothers, Daniel and William Brister and their respective families. Late in July 1847, they built shanties on the land just above the mouth of the Martinez, a little stream that runs into the Cibolo from the west. They remained only until 1854, when they moved across the San Antonio River on to the Atascosa and gave the place to Maj. R. W. Brahan. About the middle of September following the arrival of the Bristers on the Cibolo, Joseph H. Polley and his family made a settlement on a place twelve miles below the Bristers, and two miles above the Sulphur Springs opposite which stood the old mission building. Mr. Polley was one of seven adventurous spirits who, in1820 accompanied Moses Austin to San Antonio and thence back to Nacogdoches. In 1821 he came to Texas with Stephen F. Austin as one of the "original three hundred" colonists introduced by that empressario into the country, and settled in Brazoria County on the Brazos River. Although in full sympathy with the Republic of Texas in their struggle for independence from Mexican rule, he did not join the army, being, as President David G. Burnett said in a letter of instruction addressed to him, "one of the few able bodied men, possessed of sufficient courage to stay at home and protect the women and children of the land."

Old Texans

A month and a half after the arrival of Mr. Polley, James Peacock and his brother, Leander, established themselves on the west side of the creek opposite Patton's Bend and twelve miles below Mr. Polley. They were Tennesseans and bachelors. Mr. James Peacock, however, marrying in 1853. He had been a soldier under General Zachary Taylor in Mexico. His brother, Leander, was known as "Cap" and will be readily recalled by many people in San Antonio, whither, after the death of James Peacock, a few years after the war he went with his sister-in-law and her children.

This closed the immigration for that year. Counting adult males, the settlement, if we may so dignify it, consisted of nine Americans, three Mexicans, and five negroes. Cato, or Cato Morgan as he came to be known after emancipation, being the only darkey among the blacks who had the courage and the knowledge of firearms necessary to fight Indians. Living as they did, however, twelve miles apart, each of the settlers had perforce, to depend largely on himself and his immediate employees for defense against the savages. To go armed practically all the time, was the rule and necessity. But as there were then no breech loading repeaters and six shooters and pepper box revolvers had not appeared as per now, if then invented, a man on horseback who wished to be well armed, usually carried along with him a small arsenal: that is a long-barreled rifle in his hand, as many single-barreled pistols as he could find room for in a belt around his waist, a pair of large pistol holsters attached to his saddle, and a bowie knife. There was need to go thus protected, for while no attack was ever made on the settlement, in 1848, 1849, and 1850, the Indians came around on thieving excursions and drove off many horses. Each time they were pursued, and each time Cato Morgan volunteered and accompanied the pursuing party. But they were never overtaken.

In the spring of 1848 Creed Taylor and his brother-in-law Martin West settled on the creek three miles below the Sulphur Springs. Creed Taylor was even then a noted scout and Indian fighter. He had served in the army of the Texas Revolutionists of 1836, been constantly on the frontier up to the beginning of the War with Mexico and had then served with "Jack Hayes" under "Old Rough and Ready." That he was a valuable acquisition to the settlement may be easily supposed. He is yet living hale and hardy at the age of 96 in Kimble County, Texas. The populations of the Cibolo Valley was further increased by the coming, that summer, of the Lansing family, who took possession of the old Mission building and made their home in it. It was too far west for them, though and they stayed but a couple of years.

In the fall Claiborne Rector, the widowed brother-in-law of Mr. Polley, who had assisted him to move from Brazoria County and had since resided with him, built a house a quarter of a mile above Mr. Polley's and into this his brother, Pendleton Rector moved, coming from the San Marcos. Claiborne Rector had been one of the most trusted members of Deaf Smith's Spy Company, and had performed valuable services in the revolution of 1836. Pendleton Rector had also been a soldier in the Texas army, and, at San Jacinto had been so wounded as to remain slightly cripple all his life. Both were gentlemen of nerve and high moral character, and did much toward giving tone to the community in which they lived.

The next arrival in the valley was in March 1849. Then Dr. John Sutherland came and settled on a league of land owned by him opposite the Sulphur Springs. He had been in the Alamo with Travis and Crockett and their compatriots at the time it was first learned that Santa Anna and his army were approaching the fortress, but luckily for himself and his family was sent to Gonzales and the country in touch with it for reinforcements. While on his way back he was met at the Cibolo by Mexican troops and learned of the massacre. He was a gentleman of most admirable character, and because of that and his knowledge of medicine, was greatly received as a member of the little community. He died in 1867. Two of his sons, Jack Sutherland and W.T. Sutherland, still live within twelve miles of the Springs.

Sutherland Springs

A month or two after the coming of Dr. Sutherland, Mr. Joseph F. Johnson, a resident of Seguin, began the erection of a hotel at the Springs. The building was in harmony with the time, consisting of six or seven cabins placed in a row ten feet apart they and the intervening spaces being all under one roof, and only two rooms and the space between them floored with plank –the balance having dirt floors. To make the place more attractive than even "streh" palatial accommodations and the magnificent bathing made it, he built a ten-pin alley, with a hundred yards of the other building. The enterprise received, for a time, quite a large patronage from San Antonio, Seguin and Gonzalez and other places. It was while it was in full blast that a story gained circulation among the negroes in the vicinity, which brought Sulphur Springs, and particularly the black sulphur one in the front of the hotel, in exceeding bad repute among the credulous creatures.

The tale was that a young darkey from Seguin had brought a written message to Mr. Johnson. Having delivered it, he rode down the hill to the big, black sulphur spring – then twenty-five or thirty feet in diameter. Its waters boiling up through a dozen or more vents in the white quicksand that formed its bottom, and immense quantities of gas from sulphur deposits below escaping in bubbles, large and small – unsaddled and staked his horse, and then undressed, jumped feet foremost into one of the largest vents and disappeared, never again to be seen by living man. Of course it was a hoax – such being the specific gravity of the water and the expelling force of the ever rising gas that a strong man, standing erect and pulling with all his might on a beam firmly fixed underneath the surface cannot pull his head under water. Still, every darkey believed the story, and from that day to this, it is impossible to prevail on any of them who lived in the neighborhood to go into the spring, lest he or they be overtaken by the same fate which befell the darkey of 1850.Even today forty years after emancipation, no "Jim Crow" law is needed to keep them out of it.

In the fall of 1849, a couple of bachelor brothers from Nova Scotia, Dick and Henry James, established themselves and a few Mexican hirelings on a farm and ranch seven miles above the Sulphur Springs. In the same year, the military authorities of the United States established a depot of supplies for the army in Texas, at Indianola, and opened up a direct route from Victoria to San Antonio that crossing the Cibolo four miles below Sulphur Springs, followed up the west valley of that stream to an intersection with the "Old Gonzales Road" – a route which, it is said, was laid out by Santa Anna when marching east to his defeat and capture at San Jacinto. Previous to this action by the military authorities, travel between Indianola and San Antonio had been via Goliad. Now the most of it was diverted from that route and the sight of the long army trains that began to pass backward and forward through the Cibolo Valley, and of Troops moving toward the frontier promised so much protection as to be very comforting.

About the same time, preparations were made to run a stage line between Indianola and San Antonio. It got fairly into operation in the spring of 1850. Dr. Sutherland keeping the one stage stand on the Cibolo. As San Antonio had come to be the headquarters for that part of the old army sent to Texas frontier, comparatively few of the many army officers who, either as Federals or Confederates, gained destination during the war between the States, but traveled this route at one time or another and stopped at Dr. Sutherland's.

The year 1849 marked an epoch in the history of San Antonio, that is well worthy of record. In brief, it was the introduction into the markets of the city of the first American watermelons. Previous to that date, the American citizens and the few darkeys who had followed their masters that far west, had perforce to be content with a few small and insipid specimen of this fruit that were raised by Mexicans, and it goes without saying that the arrival of two wagonloads of the large sized and thoroughly ripe delicacies created a stir. The benefactor and public-spirited citizen in the case was a gentleman who afterwards became known far and wide as "Old Dan Cotter." Early in the spring of the year named he settled on the Ecleto, twelve miles east of the Sulphur Springs, and fencing in with brush a ten acre patch of white sand planted it in watermelons.

Deluge

The enterprise took up so much of his time that he never found the leisure then, or in fact, while he lived, which was many long years to put a door to the cabin he built for his good wife and children. When the watermelons ripened, he rigged up a couple of ox wagons, six yokes to the team, and at ten o'clock of a hot day in July appeared on the Main Plaza, and announced what he had for sale. The glad news spread as rapidly as that of approaching Indians would have done; the people of the city came in haste to the feast, all business was (illegible) had as many dollars in his pockets as he had brought watermelons. Owing to the distance and the slow method of transportation he was able to make but a few trips before the fruit became over ripe. But while his trade lasted it was a bonanza to him. In the shutterless cabin he first built, he reared a large family of children, several of whom are now wealthy and highly respected citizens of Wilson County.

In the spring of 1850 Creed Taylor and Martin West moved to the Ecleto. W. D. Mayes, one of the forty-niners whom the gold fever got a grip on and carried overland to California, moved into the houses vacated by them. Mr. Mayes was the father of Mrs. Thomas G. Paschal of San Antonio. Fayette Walker, once the most prominent negro politician in Bexar County if now living, will remember him as "Mawse Willie". In the same year of 1850 the Trainers and David and John Wheeler made settlements some little distance below the stage stand at the crossing of the Seguin and San Jacinto Road. Others may have come that year also, but if so, their names are not remembered.

In 1851 the deluge began, in the way of newcomers and continued without intermission until the unexampled drought of 1857, when from November of 1856, until August 3 of 1858, cornmeal was a delicacy. Flour brought up from Indianola sold at $12.00 a barrel and sometimes higher. Fortunately, there was beef in abundance and with that and coffee the people could not starve. Among the fifty-oners- that is, those coming in 1851- were G. H. McDaniel, Thomas M. Batte, D. C. Robinson, Thomas J. Peacock, John D. Wyatt, J. J. Hankinson, Dr. G. J. Houston, Ross Houston, J. M. McAlister, T. D. James, W. K. Baylor, W. R. Wiseman, W. D. Skull, J. T. Montgomery, J. F. Tiner, Levi Humphreys, James Ripley, J. A. Burnside and E. F. Potts. Better men and citizens then they never found a home in Texas. Of those coming later than 1851 and making up the white population of the valley at the beginning of the war between the States were Maj. James L. Dial. Henry Yelvington, Lem Perkins, Dorsett Harmon, Maj. R. W. Brahan, Colonel Frazier, Weir, Wickes, Rev. R. M. Currie, Edmund Barker, Elam, Floyd, Gordon. Rev —–Hamilton, Wells, S. W. McClain, James Newton, Collier, C. F. Henderson, Henry Morgan, Jesse Applewhite, Dr, William Sutherland, Rudolph Helman and a brother, Colonel Saunders, Spivey, McKee, Dr. R. Stevenson, W. F. Hughes, Rev. Robert McCoy, A.G. Pickett, Owen Murray, Asa Murray, Dr. Owens, Volrath, J. R. Plummer, T. C. Wyatt, J. G. Kilgore, Barclay, Maddox, J. W. Lilly and Tignal Jones.

Only the names of heads of families have been mentioned. Of the fifty-oners not one is still living; of the wives who came with them only Mrs. J. T. Montgomery and Mrs. W. R. Wiseman yet survive. Of the heads of families that came after 1851, there are three survivors known – Asa Murray, John McDaniel and Floyd; of their wives Mrs. R. M. Currie, Mrs. Floyd and Mrs. Henry Morgan are the only ones known to be yet alive. Among unattached persons – that is widowers, and adult bachelors without family ties in the neighborhood who lived in the valley in 1861, may be mentioned John McDaniel, L. P. Hughes, Eli Park, L.P. Lyons, W. A. Bennett, L. Buchanon, Tom Bannister and Charley Warner. Of them, the only known survivors are John McDaniel and L. P. Hughes, each of whom wears an empty sleeve to show that he was on the firing line in the troublous days of the sixties. Park and Lyons met tragic deaths in Virginia and the others have sought new and far-away pastures.

Mention has already been made of Indian incursions in 1848, 1849, and 1850. Not until 1855, and after the valley was pretty well settled, was there another alarm. A boy named McGee came in July of that year to the house of Pendleton Rector to get a cow and calf that the gentleman had in a pen. Early the next morning the cow and calf was turned out of the pen, Mr. Rector going along to get the boy fairly started. Half a mile above the present town of Lavernia, the boy noticed some mounted men galloping through the chaparral to the right of the road, and asked Mr. Rector who they were.

Savage Land

Mr. Rector no sooner caught a glimpse of the strangers, though, than he knew them to be Indians. Telling the boy so, and calling to him to follow as fast as he could, Mr. Rector wheeled the old mare he rode, and set off at her best speed back toward the house. He was totally unarmed, as he rode, he shouted loudly to imaginary friends: "Come on, boys — come on—here they are." His object being to create the impression on the minds of the Indians that a party of whites were near at hand. He had not gone 100 yards when his mare turned a summersault, and left him afoot. But springing to his feet, he continued to shout, "come on boys." and ran at the best speed his game leg would permit. As for the boy, he was riding a mule and that obstinate brute absolutely refused to follow after Mr. Rector. The Indians therefore overtook the boy, and speared him to death. Then not sure but that Rector had friends in the rear, they let him alone, and drove the large herd of horses they had gathered and galloped into the post oaks. They were followed as soon as a party could be gotten together, but as the post oaks were exceedingly boggy and there was necessarily considerable delay in beginning the pursuit, they escaped to the west side of the San Antonio River with their booty. It took (illegible) however for the alarm to subside. One day, three weeks after the murder of the McGee boy, all the people in the Lavernia neighborhood had assembled at a log house on the banks of the Cibolo which served the purposes of a church and school. How it originated nobody knew, but suddenly a report went around that a force of more than 1,000 Indians had assembled on the headwaters of the Cibolo, and were moving in a body down the creek, killing and scalping as they came. Not a man but that believed it, not a woman but expected, ere morning came to become a victim of Indian brutality. Home they went, under whip and spur to gather up their children and either find a hiding place in the woods or to gather together at this or that large house. Although long before nightfall, many cool-headed men had convinced themselves it was an absolute false alarm, quite a number of others remained in doubt until at dawn next morning a scouting party returned and gave the lie to the report. It was a day or two although a few families who had taken to the brush were found, and persuaded to return to their homes.

Many and remarkable as the differences between the past and present of the Cibolo Valley, they catch the eye and claim the attention only of the boy of then, the old men of now. Then only fields, gardens and yards were enclosed, all other land being a common range on which everybody's cattle, horses, sheep goats and hogs grazed and roamed at will. Then one might have struck a bee line from the Sulphur Spring to San Antonio and not have met a man, encountered a fence or passed in sight of a house – the only animate things to be seen on the route being birds, squirrels, rabbits, coyotes, lobos, deer, long-horned cattle, long maned and tame horses and, perhaps, now and then a panther, catamount, leopard cat, wildcat, coon, fox or opossum. Now practically all the land save that given to roads and lanes is under fence: the homes of a happy and prosperous people dot the landscape in every direction, the wild game has sought refuge in much deeper wilds as yet little trodden by the foot of man, the long-horned cattle have become Durham's and Devons, the long haired horses, Percherons and Morgans. Towns have sprung up on the sites of ancient Indian camps; the whistles of locomotives of the Gulf Shore Railroad and of many (illegible) of the day telegraph and telephone wires follow the track of the railroad, the rough log buildings that once served for school and churches have been supplanted by large and commodious frame houses and the Belles of a dozen or more handsome tall-steepled churches in country and town of a Sunday summon the devout to the worship of God.

In short civilization has banished the rudeness and wilderness of the grand ante-bellum days. The dwellers in the now peaceful valley are in touch with the world. The old log houses in which their fathers and mothers dwelt have been replaced by marvels of the ornate, in architecture, and from within the precincts of these handsome homes comes the sound of laughter and music and the rustle and swish of not simply daintily, but fashionably clad women. The side saddle, and the gentle, cross gaited horses, on each of which a mother and three or four children were wont to ride to church or festive gathering have gone out of fashion, vehicles taking their place. Whereas it used to take a day to go to San Antonio, and a day to return in, it now takes but an hour each way: and whereas in the old days the method of communication with the outside world was by letter or visit, now you send your messages by wire, or talk over the telephone. All that is lacking, in fact, to render the people of the Cibolo Valley thoroughly happy, is the Marconi system of wireless telegraphy. That established, not even the small remnants of still alive Populists will do any more kicking.

COURTESY / LostTexasRoads.com